|

|

|

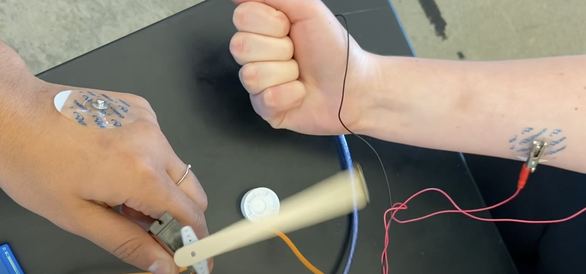

This lab activity takes students on a unique journey through the world of neuroscience and engineering to explore the complex nature of Parkinson's Disease. Students will simulate the motor symptoms of Parkinson's Disease firsthand by experiencing disruptions in motor control aimed to foster empathy for those living with the condition. Integrating biochemistry, neuroscience, and engineering principles, this lesson is a powerful tool for inspiring the next generation of scientists and empathetic individuals. Click here for access to all lesson resources.

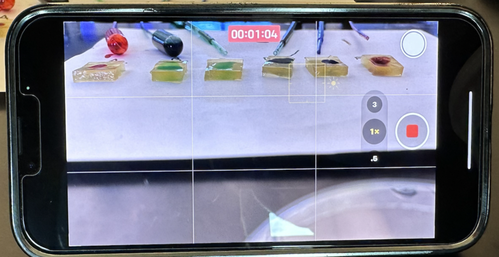

This lab activity directly tackles a pressing issue: the opioid crisis, with a spotlight on fentanyl, one of the most potent and problematic drugs out there. This isn't just any experiment; it's a timely exploration of a topic that's as relevant as it is serious, using a creative setup to model the brain's defense mechanisms against substances like fentanyl. Using simple materials to simulate the blood-brain barrier, we'll uncover why fentanyl is particularly adept at breaching this protective boundary. It's a hands-on way to grasp the complex science behind drug interactions and their impact on the brain. I'm aiming to strike a balance here—keeping it professional, yet approachable, ensuring we all grasp the gravity of the opioid epidemic while engaging with the chemistry that underlies it. This lab is more than an educational exercise; it's a chance to connect classroom learning with real-world challenges and tackle this topic head-on, learn together, and shed light on the science behind opioid toxicity. Click here for access to all lesson resources

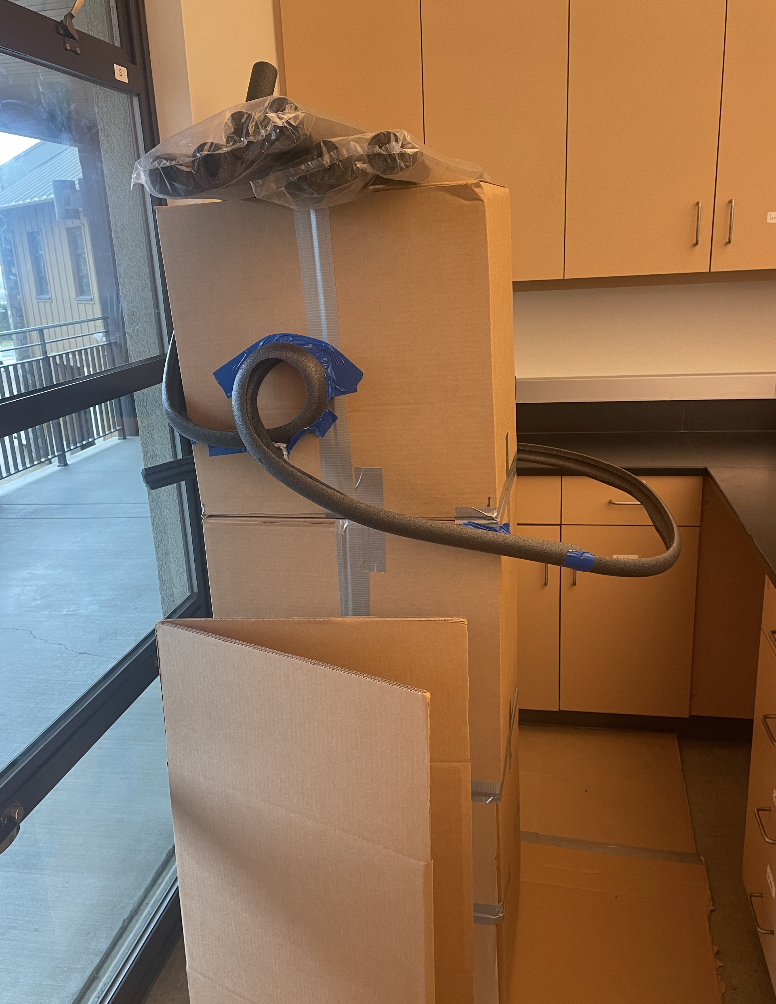

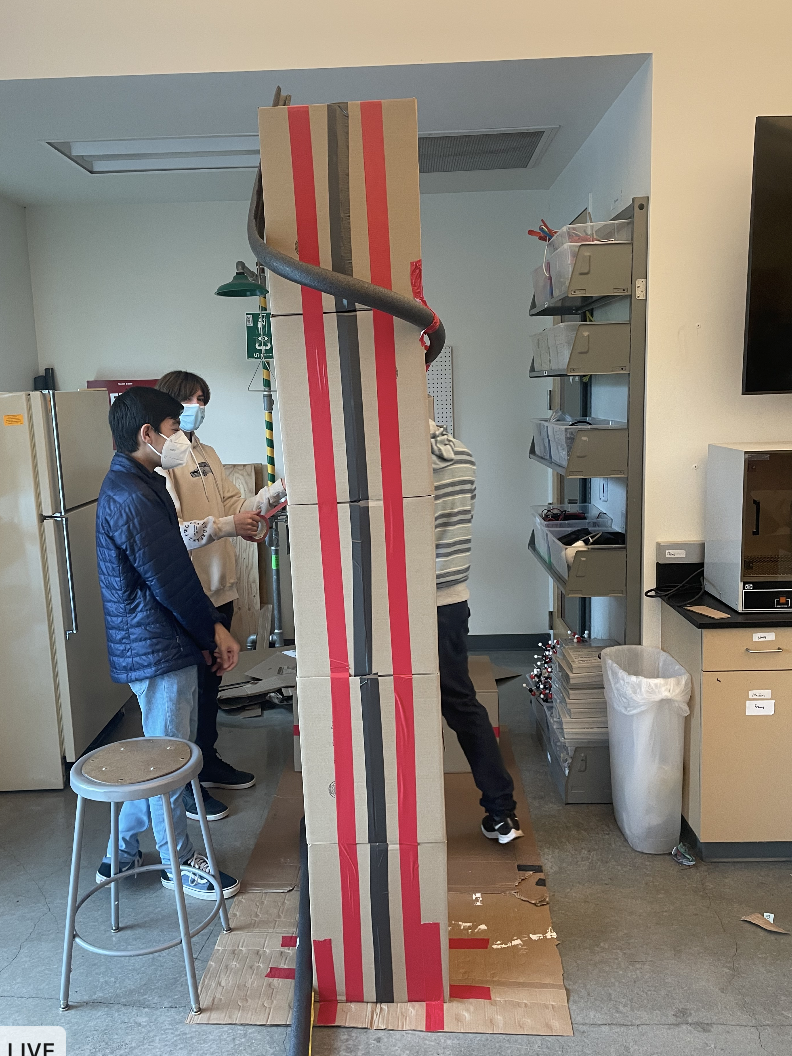

Experimenting with leveraging ChatGPT as a medium for generating code to run simple JavaScript games in p5.js. My ultimate goal is to create a system where students can use both applications to create dynamic simulations of class content (kinematics, gas behavior, forces, etc.). In the meantime I'm having a blast making these silly games in under a minute. I am teaching physics for the first time in 21 years! Beginning with a unit on conservation of energy by challenging students to create marble roller coasters using cardboard boxes and foam pipe insulator. The entire activity is based on this blog post by physics educator Ben Wildeboer. Click here for our class handbook with activity specifics and follow up inquiry cycle applications. See a few images below.

I recently discovered this amazing YouTube channel that proposes, WELL PRODUCED, video scenarios about perplexing "What if..." scenarios and then animates/describes what would occur? For example: "What if the oxygen disappeared from the world for 5 seconds?" or "What if the moon exploded?", etc. Keeping "What if" in mind, I have been struggling with hands-on labs during distance learning, and have recently been experimenting with leveraging the scenarios described in on the channel to empower "Thought Experiments" rather than forcing distance learning labs while student are not in class. I did two "What if" thought experiments this week, one in my Chemistry class, and one in my Biology class. Students LOVED THEM! The went like this:

Use "What if" thought experiments to spark curiosity about an upcoming unit (as I did above prior to a unit on Cellular Respiration), or challenge student's ability to apply learned content to a new, hypothetical situation. Either way, "What if" thought experiments have transformed engagement in my online classes this week.

|

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed