|

|

|

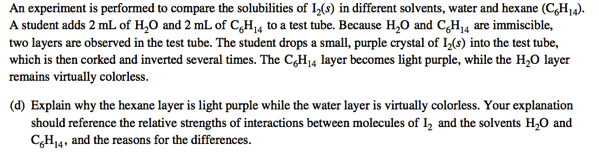

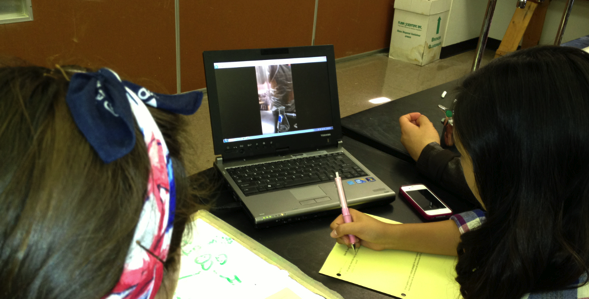

Inspired by a fabulous Dan Meyer session I attended at my school last month, I have begun the process of trying to re-frame as many released AP Chemistry problems into inquiry videos as possible. Using Dan’s 101qs/#anyqs videos as a framework, my goal is to create a video that stimulates the students to ask the desired question the problem intends to ask. Rather than posing a scenario for students, providing all the necessary information to solve it, THEN asking the question, multimedia can be harnessed to create a gradually released framework where students are naturally perplexed enough to wonder the question the problem intends to ask. Once this is achieved, further information is provided, eventually scaffolding the students through the problem-solving process. My plan is to use such videos to initiate theExplore-Flip-Apply inquiry process, use them as warm ups the day of an inquiry lab, or even as extension activities after a problem-solving session upon conclusion of a learning cycle. Below is my first attempt. To introduce this process to my students, I surprised them with a group quiz that I would have normally done with the traditional question format. First I found this released free response question from the 2012 AP Chemistry Chemistry test that fit the standards to be assessed on the quiz: Then using my iPhone, and with the help of a colleague, I recorded this video version of the question and published to YouTube: Because I posted the video to YouTube, I didn’t want students distracted by all the other garbage. To negotiate this, I created a URL that would open the video in full screen immediately. Below is how I did that: After using bit.ly to shorten the link (I chose bit.ly instead of goo.gl so I could customize the address for student ease of access during the quiz), I created and administered the below quiz: Below is a picture of the process:

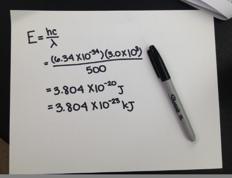

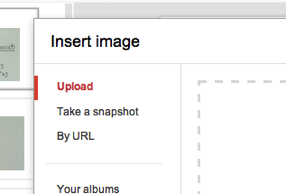

When off-loading content delivery, pairing the assignment with a Google form for reflection and critical analysis of the video/text, etc., is a powerful way to facilitate metacognition, but also gather and respond to student questions, misconceptions, etc. However, with a few simple steps, instructors can design a Google form that directs students to specific questions based on their answers, while also creating a simple and efficient way to communicate with students via email directly from the Google spreadsheet. The first video below outlines how to create a “branching” Google form, and the second video outlines how to install and use the “Form Emailer” script to facilitate easy communication with students regarding their misconceptions, questions, etc. My apologies as the below videos don’t have sound so follow them closely :) Branching Google Form Form Emailer Script As a science instructor, I find myself spending a lot of time debating, creating and reflecting on the “explore” phase of the learning cycle. Naturally, “hooking” students, building perplexity, and guiding students toward a collaborative learning objective, IMO, requires much more instructional skill than the “explain” (flip if you so choose) or “apply” phase…or at least so I thought. While the explain phase has continued to be the least emphasized part of the cycle (3-5 minute lower end Blooms delivery), I have not done a good job moving beyond the “drill and kill” tendency of the application phase of the learning cycle. While in theory, the “apply” phase calls for much more than practice, in chemistry in particular, for me, there is a tendency to get stuck in a “study hall” like environment as students struggle through problems in class. To try and bridge the gap between practice, and also promoting extension and critical investigation of problems, I did a version of Kelly Oshea’s Mistake Game. Students were given a problem, and were asked to solve that problem, but plant one common mistake, as if they are writing multiple choice item distractors. Students then viewed one another’s problems, and qualitatively identified their mistakes. I enjoyed how this activity seemed to quench the students need to practice problems, however it also forced students to reverse their role, and step into the shoes of the test writer. Not a true “extension” of their knowledge to the real world, but this activity successfully forced students to assess problems through a different lens. To accomplish this, I harnessed the “snapshot” tool in google docs (thanks to @followmolly for this tip at ISTE) to create a fluid jig saw where students created their “mistakes” and then shared them with others. Below is an outline of the process: 1. Create google presentation with one slide for each group and make the presentation public and editable by all. 2. In the presenter notes section of each slide, write unique question for each group. 3. Instruct each group to solve that question on a white sheet of paper, using a sharpie and planted one mistake. See below: 4. Using the snapshot tool, instruct each group to insert picture into the slide. See below: 5. Groups then observe one another’s slides and identified the mistake made. 6. Upon conclusion of activity, facilitate a class discussion where groups discuss the most appropriate mistake. See an example of the complete slide deck here: |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed